What started as a curiosity for machine learning during a semester abroad turned into a globe-spanning PhD adventure for Lena Stempfle—one that challenged her assumptions about research and reshaped her career.

Lena, a WASP PhD student at Chalmers University of Technology, says her time overseas hasn’t just expanded her research horizons—it reshaped her perception of what life as a researcher could be.

“I must say I never thought my PhD would be this exciting and full of opportunities,” Lena reflects with a laugh. “I feel like the image of a researcher is a bit more boring than it has proven to be.”

Lena Stempfle during a self-organized study trip to Japan in 2024, funded by WASP.

From exchange program to PhD

Lena’s academic path began in Germany, where she pursued a master’s degree in information engineering, management, and law at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). In 2019, she joined an Erasmus exchange program to Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden. That six-month stint would leave a lasting impression.

“I really enjoyed my time here. It was very different from how things work in Germany,” she recalls. That experience, combined with her growing interest in machine learning for healthcare, eventually drew her back to Chalmers and a PhD in Data Science and AI, with the specific application area healthcare.

In August 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic intensified, Lena began her doctoral studies under the WASP umbrella. Despite the global upheaval, she quickly found a research home like no other.

From the start, Lena appreciated the program’s blend of structure, freedom, and community. “WASP gave us so many opportunities to connect across the country,” she says.

Whether through national courses, summer schools, or winter conferences, the WASP network made Sweden feel smaller and collaboration more accessible.

“A PhD can be lonely if no one in your group shares your topic,” Lena says. “Knowing there were other PhD students working on similar or adjacent topics was incredibly helpful.”

WASP also helped her broaden her horizons. She attended world-leading conferences like ICML in Hawaii and NeurIPS in New Orleans, often combining the conferences with industry visits to places like IBM in New York and a self-organized study trip to Japan.

“I know many other PhD colleagues in different countries and positions where courses, conferences, or research contacts are just not available or hard to get,” Lena notes. “They spend a lot of their time organizing their PhD life. I’m so grateful for the WASP community, with the network in Sweden and all the possibilities we have.”

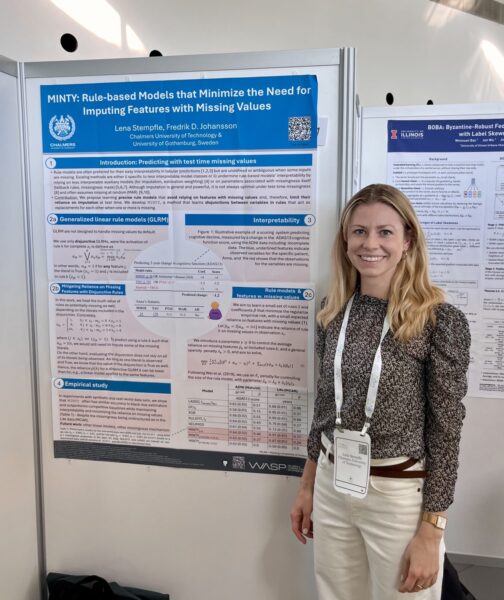

Society for Artificial Intelligence and Statistics’ (AISTATS) meeting in Valencia, 2024.

Research with Real-World, Incomplete Data

Lena’s research focuses on a pressing challenge in healthcare data science: how to make reliable predictions when key patient values are missing.

“In healthcare, values in tabular data, for example electronic healthcare records, are often missing,” she explains. “It can be due to unavailable machinery, human error, or differences between hospitals. But most machine learning models assume the data is complete when making predictions. That’s a big problem.”

Lena’s research aims to develop methods that achieve high predictive performance when the input data has missing values, with the goal of representing the model output in a simple, comprehensible way for domain experts.

Another core theme in Lena’s research is interpretability. Models should be understood by the clinicians who use them, she says.

“Doctors are legally responsible for their decisions—they can’t just say ‘the AI told me so.’ They need to understand how a prediction was made,” she says. “So, we design models that are not only accurate but also comprehensible.”

Healthcare often uses risk scores—which assign points to a patient based on factors like their age, their blood pressure, and whether they have diabetes or previous cognitive impairment. All these factors might be used to assess a patient’s risk of say, Alzheimer’s.

But what if a key value is missing, such as age? Running the risk model without a patient’s age would skew the results, but putting in an assumed age could result in bias.

Instead, Lena’s research suggests better ways of replacing that missing value with another value or “feature that has a similar predictive performance than the one missing, without inputting or guessing the value of the originally missing one,” says Lena. For example, heart rate can serve as an indicator of age if age is missing. This can tweak an algorithm to be more accurate despite the missing information.

Building global research collaborations

In 2024, Lena took her research on the road. Supported by WASP, she spent two months at Inria, the French National Institute for Research in Digital Science and Technology, in Montpellier. There, she worked with senior researcher Julia Josse on theoretical frameworks for handling missing values and began collaborating with TraumaBase, a clinical network of ICU and trauma centers across France.

“Since we take inspiration from real-world clinical applications, it is wonderful to have access to a network of clinicians and be able to collaborate this way,” Lena says.

Later that year, she travelled to Boston for a five-month research stint at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). She joined the lab of Marzyeh Ghassemi, which focuses on fairness in machine learning for healthcare. The shift in focus allowed Lena to explore new questions around how predictive models perform across different demographic groups, and how to ensure the models won’t discriminate based on age, ethnicity, or other factors.

“We focused more on evaluating foundation models for their risk of memorizing personal health data—ensuring that if we deploy these models in healthcare, they won’t memorize legally-protected or sensitive patient information,” she said.

These international experiences were more than academic exercises. They helped Lena build professional networks and lasting collaborations.

“I’m really happy I went on these research stints,” she says. “I still work closely with the clinicians in France, and I’m wrapping up several projects with MIT PhD colleagues.”

Lena Stempfle at her research stint to MIT, Boston, in 2024.

What’s next

Lena is on track to defend her thesis in August 2025. While she hasn’t decided on her next step, she’s open to both academia and industry.

A postdoc abroad, to further her international experience, is one option. “In AI and machine learning, it’s important to gain experience in different environments,” she says. “But eventually it would be nice to come back to Sweden.” The alternative would be a research scientist role in industry, ideally in a field that maintains close ties to high-impact, real-world problems.

No matter where she goes next, Lena knows the foundation she built during her WASP PhD will continue to guide her.

Her words of advice to future WASP PhD students?

First, she recommends “interviewing” your potential supervisor. “It’s important to find out whether you can work well together, as the supervisor often plays a key role—not only as a sparring partner but also as a source of support, connections (e.g., for research visits), and guidance throughout the PhD,” says Lena.

She also recommends exploring different topics before committing to a specific research area. “This gives you a broader perspective and helps you find what truly excites you,” she says.

Finally, Lena hopes students will embrace opportunities. “Don’t underestimate how exciting this journey can be. I never imagined I’d get to work with people I’d long admired from afar, or that my research could take me to places like MIT. It’s been an incredible experience.”

Published: April 28th, 2025

[addtoany]